The Trump Administration has signaled that it plans to expand energy production, expedite energy permitting, and ‘roll-back’ regulations and practices that impede growth. As part of this effort, Mr. Trump has named Lee Zeldin, a former GOP member of Congress, to lead the EPA.

Mr. Trump has stated that Mr. Zeldin wishes to “ensure fair and swift deregulatory decisions” while maintaining “the highest environmental standards, including the cleanest air and water on the planet.’’ Further, Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy, heads of the so-called Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE, have vowed to work with the Trump Administration to use executive action “to pursue three major kinds of reform: regulatory rescissions, administrative reductions and cost savings.”

Category: Trump Administration

The Push To Unleash American Energy

On January 20, 2025, the day of the inauguration, President Trump signed Executive Order 14154, Unleashing American Energy. Through the EO, President Trump seeks to “encourage energy exploration and production on Federal lands and waters … in order to meet the needs of our citizens and solidify the United States as a global energy leader long into the future.” He ordered an immediate review of “all existing regulations … and any other agency actions … to identify those agency actions that impose an undue burden on the identification, development, or use of domestic energy resources.” He further ordered that agencies must “expedite permitting approvals” to achieve this overall goal.

The relevant federal agencies have heard the call. Doug Burgum, the Secretary of the Interior, issued Order No. 3418 to implement the EO. In it, Secretary Burgum ordered steps be taken to reduce “barriers to the use of Federal lands for energy development” and that leases cancelled during the Biden Administration be reinstated. Chris Wright, the Secretary of the Department of Energy, criticized net-zero policies, stating that they threaten the reliability of our energy system and achieve “precious little in reducing global greenhouse gas emissions.” He resumed consideration of pending applications to export American liquefied natural gas (LNG). Towards that end, he announced a new export authorization for the Commonwealth LNG project proposed for Cameron Parish, Louisiana and provided an export permit extension for Golden Pass LNG Terminal, currently under construction in Sabine Pass, Texas

EPA is also involved. Administrator Zeldin announced an initiative, titled Powering the Great American Comeback, which included his ‘five pillars’ approach. The ‘pillars’ include Restoring American Energy Dominance and Permitting Reform, Cooperative Federalism, and Cross-Agency Partnership. Energy produced in America “is far cleaner than energy produced overseas” and is better for the environment because “we do it better here.” However, the cost and length of time to obtain necessary permits is a potential impediment to achieving these goals. EPA will “bring down that timeline [to] make sure it doesn’t take as long to get a permit.”

Administrator Zeldin also announced that EPA will reconsider over thirty regulations. These include the standards of performance for oil and gas facilities (Subparts OOOOb/c) and the effluent limitations guidelines and standards (ELGs) for wastewater discharges for oil and gas extraction facilities. EPA will also reconsider regulations on power plants (the Clean Power Plan 2.0).

Overall, though, perhaps the most important one is the reconsideration of the 2009 Endangerment Finding and all of the regulations and actions that rely on it. In the Endangerment Finding, EPA concluded that carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and other greenhouse gases threaten public health and welfare. While the Finding itself did not impose any requirements, it was a “prerequisite for implementing greenhouse gas emissions standards for vehicles and other sectors.” Secretary Wright stated that the Finding “has had an enormously negative impact on the lives of the American people. For more than 15 years, the U.S. government used the finding to pursue an onslaught of costly regulations – raising prices and reducing reliability and choice on everything from vehicles to electricity and more.”

In addition to its regulatory impact, EPA provided other reasons for the reconsideration. First, when EPA announced the Finding, it indicated that, by itself, it did not impose any costs and that EPA could not consider future costs when making the Finding. However, EPA has subsequently relied on the Finding as part of its justification for certain regulations with an aggregate cost of more than one trillion dollars. Second, the Finding itself acknowledged significant uncertainties in the science and assumptions used to justify the decision but EPA has never sought comment on major developments in innovative technologies, science, economics, and mitigation that may impact the Finding. Finally, major Supreme Court decisions, including Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, have provided new guidance on how EPA should interpret statutes to discern Congressional intent and ensure that its regulations follow the law.

EPA, and the other federal agencies reviewing their existing regulations and prior actions to implement the EO, must exercise some caution in changing policies. In very general terms, an agency must indicate an awareness that it is changing position, show that the new policy is permissible under the statute, indicate that the new policy is better, and provide reasons for adoption of the new policy. In light of Loper Bright, an agency would likely have to show that the new policy is not just permissible but in line with the ‘best reading’ of the statute. Overall, the agency must provide a reasoned explanation for the change. They must also follow the Administrative Procedure Act. To amend or revoke a rule, notice and comment are required and decisions are subject to judicial review. The reconsideration process will take some time and the outcome is not at all certain due to the ongoing threat of litigation.

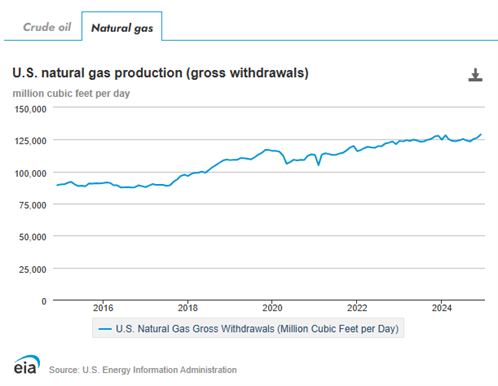

An increased emphasis on the domestic production of oil and gas and a decline in regulatory burdens are certainly welcome to the oil and gas industry and those related industries that depend on fossil fuels. Oil and gas production, which is higher now than at the start of the pandemic (see figures below), can only reach new heights.

A Good Place To Start

The Trump Administration has signaled that it plans to expand energy production, expedite energy permitting, and ‘roll-back’ regulations and practices that impede growth. As part of this effort, Mr. Trump has named Lee Zeldin, a former GOP member of Congress, to lead the EPA.

Mr. Trump has stated that Mr. Zeldin wishes to “ensure fair and swift deregulatory decisions” while maintaining “the highest environmental standards, including the cleanest air and water on the planet.’’ Further, Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy, heads of the so-called Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE, have vowed to work with the Trump Administration to use executive action “to pursue three major kinds of reform: regulatory rescissions, administrative reductions and cost savings.”

Trump, Part Two

The second Trump Administration will likely usher in a pitched battle between its attempt to ‘roll-back the Biden Administration’s environmental rules and policies and environmentalists’ defense of those same rules and policies. The outcome is anything but clear.

The Biden Administration still has some time and power to cement its legacy. In this interim transition period, it can, among other things, deny requests for reconsideration of promulgated rules, grant petitions of objection to Title V permits, and seek expedited rulings in multiple court cases across the country. It can also finalize proposed rules and policies. However, those actions can be undone, delayed, or stymied once the Trump Administration assumes control of the EPA and the Department of Justice.

Continue reading “Trump, Part Two”A Return to Regulation?

The prospect of a Biden Administration signals the likely return to active and aggressive regulation of environmental matters. In a fashion similar to the Trump Administration’s approach to Obama-era regulations, the Biden Administration has already vowed to not only reverse Trump-era de-regulation but go beyond the Obama Administration’s regulatory efforts.

Perhaps the most glaring example is addressing what the Biden-Harris Transition web-site calls the “existential threat of climate change.” Mr. Biden promises to “recommit the United States to the Paris Agreement on climate change” and to “go much further than that” by “lead[ing] an effort to get every major country to ramp up the ambition of their domestic climate targets.” Indeed, Mr. Biden pledges to “put the United States on an irreversible path to achieve net-zero emissions, economy-wide, by no later than 2050.”

The Paris Agreement calls for “holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels” through nationally determined contributions (NDC) to carbon emission reductions. The United States’ NDC was a 26-28 per cent reduction below its 2005 level by 2025. According to EPA, gross GHG emissions were reduced between 2005 and 2018 from 7,392 MMT CO2 Eq. to 6,677 MMT CO2 Eq.

It is unknown at this time to what extent Mr. Biden will “ramp up” the United States’ already ambitious climate targets or exactly how Mr. Biden intends to achieve the “ramp up.” He has stated that he would invest billions in clean energy development, that he would transition away from the oil industry by 2050, and that he would phase out or end fracking on federal lands. It is also likely that Mr. Biden would reverse the Trump Administration’s roll-back of the oil and gas sector methane rule.

Another example relates to environmental justice. Mr. Biden states that he wants to “ensure that environmental justice is a key consideration in where, how, and with whom we build” the clean energy infrastructure and go about “righting wrongs in communities that bear the brunt of pollution.” EPA defines environmental justice as the “fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.”

Mr. Biden does not provide specifics but does state that a Biden Administration will create “good, union, middle-class jobs in communities left behind,” presumably in clean energy endeavors. The creation of jobs in the clean energy sector may be how he intends to right the wrongs in potentially over-polluted communities, but it is more likely that there will be a greater push to limit or restrict industrial development in such areas.

There are numerous other Trump-era executive orders and regulations that a Biden Administration will likely address. As to the executive orders, they are easily reversed and Mr.; Biden has signaled he plans to do so. As to promulgated regulations, EPA must proceed through the notice-and-comment requirements imposed by the Administrative Procedure Act. However, regulations that are finalized in the last days of the Trump Administration may be subject to repeal under the Congressional Review Act, which was used in 2017 to repeal several Obama-era regulations. Although there is much speculation at this time, it is likely that the de-regulatory agenda pushed by the Trump Administration will be replaced with a re-regulatory agenda under a Biden Administration. To ensure some growth opportunities remain, industrial concerns will have to oppose the Biden agenda as assertively as the environmental groups opposed the Trump agenda.

The End of Regulation by Guidance Document?

EPA has issued a final rule governing its issuance of guidance documents, declaring that the Rule will lead to enhanced transparency and help ensure that guidance documents are not improperly treated as legally binding requirements by the EPA or by the regulated community. In many instances over the years, guidance documents were issued without public input, even though the policy or interpretation in the guidance document created binding requirements applicable to the regulated community. This Rule ends that practice.

On October 9, 2019, President Trump issued an executive order, “Promoting the Rule of Law Through Improved Agency Guidance Documents.” It declared that agencies sometimes used guidance documents “to regulate the public without following the rulemaking [that is notice and comment] procedures of the” Administrative Procedure Act. It directed that agencies must treat guidance documents as non-binding both in law and in practice, take public input into account in formulating guidance documents, and make guidance documents readily available to the public.

According to EPA, the Rule meets these requirements, and more. The Rule provides definitions of “guidance document” and “significant guidance document,” minimum requirements for a “guidance document” and additional requirements for “significant guidance documents,” procedures for the public to petition the Agency for modification or withdrawal of guidance documents, and an online portal (the EPA Guidance Portal) to identify EPA guidance documents for the public.

A “guidance document” is a statement of general applicability, intended to have future effect on the behavior of regulated parties, that sets forth a policy on a statutory, regulatory, or technical issue, or an interpretation of a statute or regulation. There are a few exclusions form this broad definition, such as rules subject to notice and comment and rules of agency procedure and practice or internal guidance not intended to have substantial future effect on the behavior of regulated parties. Generally, a “significant guidance document” is one that may reasonably be anticipated to lead to an annual effect on the economy of $100 million or more.

All guidance documents must, among other things, include the term “guidance,” include the citation to the statute or regulation to which the guidance document applies or which it interprets, and avoid mandatory language such as ‘shall’ or ‘must.’ Further, it must include a disclaimer that the contents do not have the force and effect of law and that it does not bind the public in any way. Importantly, any guidance document issued by an EPA Regional Office must receive concurrence from an appointed EPA official at EPA headquarters. A significant guidance document must adhere to these requirements, plus it must be subject to notice and comment before finalization.

EPA also included a provision allowing any member of the public to petition EPA for the modification, withdrawal, or reinstatement of a guidance document. EPA will make information about petitions received available to the public and indicated that it should respond to a petition in no more than 90 calendar days after receiving the petition.

Finally, the Rule requires that all guidance documents be included in the EPA Guidance Portal. The Portal currently exists (www.EPA.gov/guidance) and contains the documents meeting the definition of a “guidance document.” The web-page contains the disclaimer that EPA’s guidance documents lack the force and effect of law agency and that it may not cite, use, or rely on any guidance that is not included in the Portal. The executive order and the Rule allow the issuance and use of guidance documents while providing public input and access and general procedures for issuance. Of greater significance and importance to the regulated community, there is some relief from the use of binding guidance documents issued without public knowledge or input.

EPA’s 500th Day Victory Lap

On the 500th day of the Trump Administration, EPA touted its “notable policy achievements,” highlighting nine such achievements in a “promises made, promises kept” format. However, some of the noted achievements are works in progress and perhaps need more concrete results before a ‘mission accomplished’ banner is hung at EPA headquarters.

The nine ‘achievements’ listed by EPA include: withdrawing from the Paris Climate Agreement, ensuring clean air and water, reducing burdensome government regulations, repealing the so-called “Clean Power Plan,” repealing the Waters of the United States Rule, promoting energy dominance, promoting science transparency, ending ‘sue and settle,’ and promoting certainty to the auto industry. Continue reading “EPA’s 500th Day Victory Lap”

EPA Enforcement In The Coming Years

EPA’s enforcement presence has been reduced over the last several years. This trend will continue during the Trump Administration as EPA re-defines its relationship with states and tribes. Even so, EPA has announced an enforcement approach that will maintain it as a formidable enforcer of our environmental laws.

According to EPA’s web-site, EPA’s budget was $10.3B in FY 2010, $8.1B in in FY 2016, and $8.06B in FY 2017. For those same years, EPA’s employee count was 17,218, 14,779, and 15,408, respectively. So, EPA’s budget and employee count were on a downward trend during the Obama years.[1] Continue reading “EPA Enforcement In The Coming Years”

The Administration Restrains Itself

The Trump administration has recently signaled a retrenchment in agency actions. These voluntary actions curtail the administrative agency from exercising powers or authority beyond what may be provided to it under applicable statutes and regulations.

The attorney general issued a memorandum to all Department of Justice components in November stating that the department will no longer engage in the practice of issuing guidance documents that effectively create rights or obligations binding on persons or entities outside the executive branch without undergoing the rulemaking process. The memorandum barred any guidance documents of general applicability and future effect that are designed to advise parties outside the executive branch about legal rights and obligations falling within the department’s regulatory or enforcement authority.

When issuing guidance documents, the department was instructed, among other things, to identify the document as guidance and clearly state that they have no legally binding effect on persons or entities outside the federal government. Also, guidance documents should not be used for the purpose of coercing persons or entities outside the federal government into taking any action or refraining from taking any action beyond what is required by the terms of the applicable statute or regulation.

As to the Department of Justice, this will end the practice of issuing guidance documents that have the effect of binding anyone outside of the government, unless the proper rulemaking procedures are followed. It is unclear whether the memorandum applies outside of the Department of Justice. Regardless, in addition to its public efforts, EPA has quietly taken two actions that voluntarily restrict its ability to inject itself into state permitting issues.

First, in a memorandum posted on EPA’s website in December relating to the pre-construction analysis of New Source Review applicability, Administrator Scott Pruitt announced that EPA will no longer delve into, or “second-guess,” the pre-construction applicability analysis submitted or performed by an applicant. Thus, when an applicant performs the applicability analysis in accordance with the calculation procedures in the regulations and follows the applicable recordkeeping and notification requirements, that owner or operator has met the regulations. In such cases, EPA will not substitute its judgment for that of the applicant’s emissions projections. Essentially, this action reverses a prior policy in which EPA asserted the right to require additional analysis despite the applicant’s projections or compliance with calculation protocols.

Secondly, Administrator Pruitt issued two orders in October denying petitions for objections to Title V air permits issued by state agencies. Under the Clean Air Act, any person may petition the EPA to object to the terms and conditions within a state-issued Title V permit. Title V permits usually contain requirements from the pre-construction Prevention of Significant Deterioration (PSD) Program. Over the last several years, citizen groups have successfully petitioned EPA to issue objections to PSD permit conditions included in Title V permits. These two decisions state that the petition for objection process is not the proper forum or method to object to PSD requirements. Instead, the state’s administrative and judicial review process should be utilized.

These actions are seen by many as a departure from the recent past, in which agencies wielded authority without appropriate limitations. Certainly, they suggest that agencies will now act in a more restrictive manner.

EPA Unveils Framework For Industry Input on Regulations

Since the beginning of the Trump administration, many of the rules issued by the Obama administration, such as the Clean Power Plan and the Clean Water Rule, have been targeted for review. Scott Pruitt and EPA have been in roll-back and repeal mode. However, with the newly announced Smart Sectors Program, EPA seems to be taking a positive approach to dealing with industry and the regulated community instead of merely dealing with previously issued rules. Continue reading “EPA Unveils Framework For Industry Input on Regulations”