The Trump Administration has signaled that it plans to expand energy production, expedite energy permitting, and ‘roll-back’ regulations and practices that impede growth. As part of this effort, Mr. Trump has named Lee Zeldin, a former GOP member of Congress, to lead the EPA.

Mr. Trump has stated that Mr. Zeldin wishes to “ensure fair and swift deregulatory decisions” while maintaining “the highest environmental standards, including the cleanest air and water on the planet.’’ Further, Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy, heads of the so-called Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE, have vowed to work with the Trump Administration to use executive action “to pursue three major kinds of reform: regulatory rescissions, administrative reductions and cost savings.”

Tag: politics

WOTUS Redefined Again!

By: John B. King

The Supreme Court’s ruling in Sackett v. EPA continues to dominate discussions regarding the scope of jurisdiction over adjacent wetlands. Now, the Corps and EPA seek to codify that ruling into the regulatory definition of ‘waters of the United States.’

In Sackett, the Supreme Court adopted Justice Scalia’s opinion in its prior Rapanos decision. It held that the Clean Water Act extends only to those wetlands that are as a practical matter indistinguishable from waters of the United States. The Corps must establish first, that the adjacent body of water constitutes ‘waters of the United States’ (i.e., a relatively permanent body of water connected to traditional interstate navigable waters) and second, that the wetland has a continuous surface connection with that water, making it difficult to determine where the water ends and the wetland begins. Sackett v. EPA, 143 S.Ct. 1322, 1341 (20243).

Continue reading “WOTUS Redefined Again!”EPA’s Regulatory Roll-Back

In March 2025, Administrator Zeldin announced that EPA will reconsider a number of regulations in order to advance various executive orders issued by President Trump and fulfill EPA’s own Powering the Great American Comeback Initiative. These efforts include the 2024 ambient air standard for particulate matter, the 2009 endangerment finding, and the scope of jurisdiction over ‘adjacent wetlands after the Supreme Court’s 2023 decision in Sackett.

In the Biden Administration, EPA lowered the National Ambient Air Quality Standard for particulate matter, the PM 2.5 NAAQS. The standard was reduced to levels that were close to background levels in some areas. EPA announced it is “revisiting” the lower standard because, among other things, the lower standard “raised serious concerns from states across the country and served as a major obstacle to permitting.”

Continue reading “EPA’s Regulatory Roll-Back”The Push To Unleash American Energy

On January 20, 2025, the day of the inauguration, President Trump signed Executive Order 14154, Unleashing American Energy. Through the EO, President Trump seeks to “encourage energy exploration and production on Federal lands and waters … in order to meet the needs of our citizens and solidify the United States as a global energy leader long into the future.” He ordered an immediate review of “all existing regulations … and any other agency actions … to identify those agency actions that impose an undue burden on the identification, development, or use of domestic energy resources.” He further ordered that agencies must “expedite permitting approvals” to achieve this overall goal.

The relevant federal agencies have heard the call. Doug Burgum, the Secretary of the Interior, issued Order No. 3418 to implement the EO. In it, Secretary Burgum ordered steps be taken to reduce “barriers to the use of Federal lands for energy development” and that leases cancelled during the Biden Administration be reinstated. Chris Wright, the Secretary of the Department of Energy, criticized net-zero policies, stating that they threaten the reliability of our energy system and achieve “precious little in reducing global greenhouse gas emissions.” He resumed consideration of pending applications to export American liquefied natural gas (LNG). Towards that end, he announced a new export authorization for the Commonwealth LNG project proposed for Cameron Parish, Louisiana and provided an export permit extension for Golden Pass LNG Terminal, currently under construction in Sabine Pass, Texas

EPA is also involved. Administrator Zeldin announced an initiative, titled Powering the Great American Comeback, which included his ‘five pillars’ approach. The ‘pillars’ include Restoring American Energy Dominance and Permitting Reform, Cooperative Federalism, and Cross-Agency Partnership. Energy produced in America “is far cleaner than energy produced overseas” and is better for the environment because “we do it better here.” However, the cost and length of time to obtain necessary permits is a potential impediment to achieving these goals. EPA will “bring down that timeline [to] make sure it doesn’t take as long to get a permit.”

Administrator Zeldin also announced that EPA will reconsider over thirty regulations. These include the standards of performance for oil and gas facilities (Subparts OOOOb/c) and the effluent limitations guidelines and standards (ELGs) for wastewater discharges for oil and gas extraction facilities. EPA will also reconsider regulations on power plants (the Clean Power Plan 2.0).

Overall, though, perhaps the most important one is the reconsideration of the 2009 Endangerment Finding and all of the regulations and actions that rely on it. In the Endangerment Finding, EPA concluded that carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and other greenhouse gases threaten public health and welfare. While the Finding itself did not impose any requirements, it was a “prerequisite for implementing greenhouse gas emissions standards for vehicles and other sectors.” Secretary Wright stated that the Finding “has had an enormously negative impact on the lives of the American people. For more than 15 years, the U.S. government used the finding to pursue an onslaught of costly regulations – raising prices and reducing reliability and choice on everything from vehicles to electricity and more.”

In addition to its regulatory impact, EPA provided other reasons for the reconsideration. First, when EPA announced the Finding, it indicated that, by itself, it did not impose any costs and that EPA could not consider future costs when making the Finding. However, EPA has subsequently relied on the Finding as part of its justification for certain regulations with an aggregate cost of more than one trillion dollars. Second, the Finding itself acknowledged significant uncertainties in the science and assumptions used to justify the decision but EPA has never sought comment on major developments in innovative technologies, science, economics, and mitigation that may impact the Finding. Finally, major Supreme Court decisions, including Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, have provided new guidance on how EPA should interpret statutes to discern Congressional intent and ensure that its regulations follow the law.

EPA, and the other federal agencies reviewing their existing regulations and prior actions to implement the EO, must exercise some caution in changing policies. In very general terms, an agency must indicate an awareness that it is changing position, show that the new policy is permissible under the statute, indicate that the new policy is better, and provide reasons for adoption of the new policy. In light of Loper Bright, an agency would likely have to show that the new policy is not just permissible but in line with the ‘best reading’ of the statute. Overall, the agency must provide a reasoned explanation for the change. They must also follow the Administrative Procedure Act. To amend or revoke a rule, notice and comment are required and decisions are subject to judicial review. The reconsideration process will take some time and the outcome is not at all certain due to the ongoing threat of litigation.

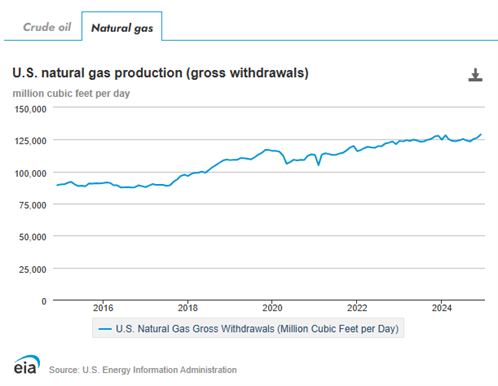

An increased emphasis on the domestic production of oil and gas and a decline in regulatory burdens are certainly welcome to the oil and gas industry and those related industries that depend on fossil fuels. Oil and gas production, which is higher now than at the start of the pandemic (see figures below), can only reach new heights.

A Good Place To Start

The Trump Administration has signaled that it plans to expand energy production, expedite energy permitting, and ‘roll-back’ regulations and practices that impede growth. As part of this effort, Mr. Trump has named Lee Zeldin, a former GOP member of Congress, to lead the EPA.

Mr. Trump has stated that Mr. Zeldin wishes to “ensure fair and swift deregulatory decisions” while maintaining “the highest environmental standards, including the cleanest air and water on the planet.’’ Further, Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy, heads of the so-called Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE, have vowed to work with the Trump Administration to use executive action “to pursue three major kinds of reform: regulatory rescissions, administrative reductions and cost savings.”

Trump, Part Two

The second Trump Administration will likely usher in a pitched battle between its attempt to ‘roll-back the Biden Administration’s environmental rules and policies and environmentalists’ defense of those same rules and policies. The outcome is anything but clear.

The Biden Administration still has some time and power to cement its legacy. In this interim transition period, it can, among other things, deny requests for reconsideration of promulgated rules, grant petitions of objection to Title V permits, and seek expedited rulings in multiple court cases across the country. It can also finalize proposed rules and policies. However, those actions can be undone, delayed, or stymied once the Trump Administration assumes control of the EPA and the Department of Justice.

Continue reading “Trump, Part Two”Supreme Court Deals a Blow to the Administrative State

The Supreme Court has overruled Chevron, its forty-year-old decision which has allowed administrative agencies to impose their regulatory will on industries, small businesses, and individuals by requiring that courts defer to an agency’s interpretation of a statute. According to EPA Administrator Regan, the decision “hits EPA extremely hard.”

In general terms, Chevron provides guidelines for a court to review an agency’s action pursuant to an act of Congress using a two-step framework. First, a court must assess whether Congress, in the statute, has spoken directly to the issue at hand and, if so, that is the end of the inquiry as the clear will and intent of Congress must be followed. However, if the statute is silent or ambiguous as to the agency action at issue, the court must, as the second step, defer to the agency’s interpretation if it is based on a permissible construction of the statute. As many statutes are silent or ambiguous as to an issue, Chevron allowed agencies to wield great power to act as long as the action was based on a permissible reading, even if the court did not necessarily agree with that reading.

Continue reading “Supreme Court Deals a Blow to the Administrative State”